By: Ahmed Shawky Elattar

Since the moment he opened his eyes to life, Sabr Abdel Kafi, a sixty-year-old farmer, has lived in the city of Burullus, and he has rarely left it.

Burullus, located in the Kafr El Sheikh Governorate of the Delta region, is in the extreme north of Egypt, and it overlooks the Mediterranean Sea. Therefore, most of its people live on agriculture and fishing.

Sabr inherited an acre of land from his father in the fertile agricultural lands of the Nile Delta. He worked hard to cultivate his land with vegetables, and he lived next to it with his wife and three children. He would plow his land with his axe at the first light of day every day, and he would harvest its bounty at the end of each season.

One night in the winter of 2011, Sabr was surprised to find that his land had become salty due to the infiltration of seawater into the soil. He recalls saying: “It was a shock. Every time we dug, we found salty water. The land had “corrupted”. This means that it has become worthless. What will we leave for our children and grandchildren?”

The man resorted to a method that farmers in the Delta region have been using to treat salt-affected land, adapting to a situation that is beyond their control. Abdul Kafi dug up half of his land and filled it in with the other half to save it from salting. It returned to being suitable for agriculture again, while he turned the dug-up part into a fish farm.

Sabr adds: “We saved what we could save, and the crop and fish farm yields are good. We somewhat reduced the loss.”

Sabr, like other Delta farmers, did not know that climate change played a major role in what befell their lands and threatened their livelihoods. It could also force their grandchildren in the future to migrate from their coastal city, leaving behind their ancestors’ land flooded with water.

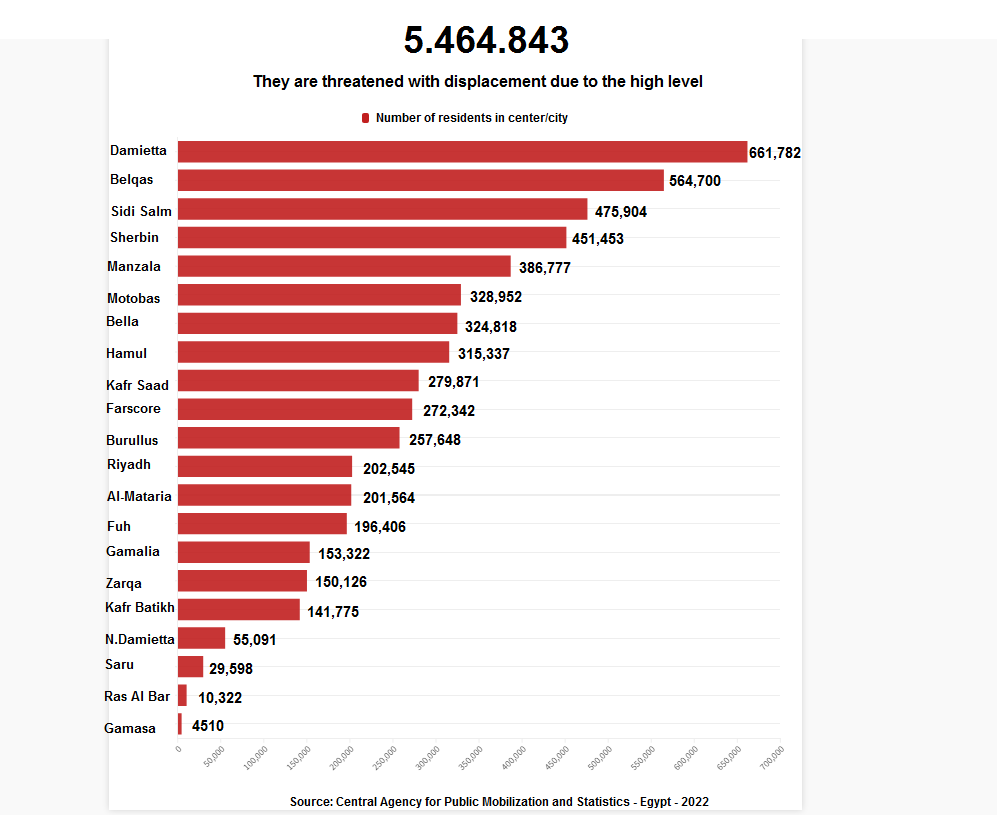

This data-driven investigation reveals how slowing down the achievement of global climate goals could lead to the exacerbation of global warming, a rise in sea level by 1 meter by the end of the century, threatening 21 Egyptian cities in the Delta region with flooding, and affecting the stability of the livelihoods of more than 5 million Egyptians living in three of the most important agricultural governorates of Egypt.

Sea level rise

Climate change is a crisis that is leading to a number of risks, from extreme heat waves and droughts, to floods and extreme weather events. However, one of the most dangerous consequences of climate change is the rise in sea levels.

According to NASA, there are several factors that contribute to sea level rise: thermal expansion of the oceans, melting of glaciers and ice sheets, all of which are caused by climate change and the rise in average global temperatures, with minor contributions from changes in terrestrial water storage.

The Earth’s temperature has risen by 1.1 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels over the past century, due to human activity and the burning of fossil fuels.

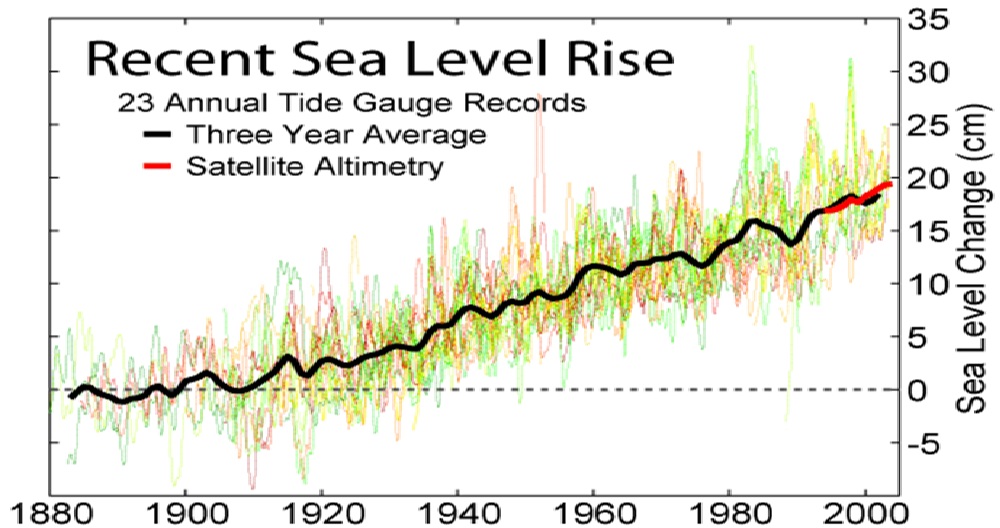

In parallel, the average global sea level has risen by 20 centimeters since the beginning of the 20th century to 2018, and is continuing to accelerate. Half of this rise occurred during the past three decades, according to the second assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015, commits the parties to it to work to keep the average increase in the planet’s temperature below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and to target limiting the increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius only.

According to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, published in August 2021, every tenth of a degree we exceed above 1.5 degrees Celsius, makes the climate damage much greater, and makes it more difficult to contain the crisis, or adapt to its effects.

For example, under 1.5 degrees Celsius, the Arctic sea ice will remain in the summer, but under 2.0 degrees Celsius, the likelihood of sea ice melting increases tenfold.

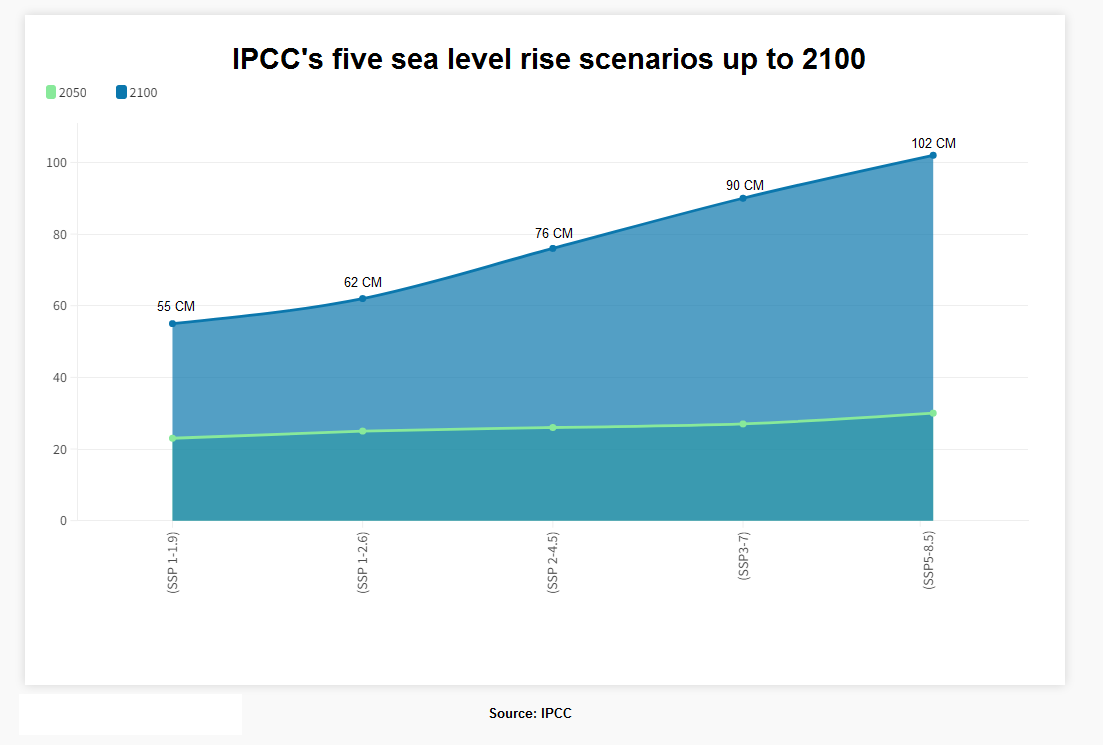

In its Sixth Assessment Report published last year, IPCC modeled five different scenarios for how sea levels will rise by 2100, based on how successful humanity is in mitigating the climate crisis and phasing out fossil fuels.

The most optimistic scenario is that if the world commits to the 1.5-degree Celsius goal by 2050, sea levels will rise by 28-55 centimeters by 2100.

In the most pessimistic scenario, sea levels will rise by 101 centimeters or more by the end of the century.

The head of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Jim Skea, told us: “If current climate policies continue, we could see an increase in temperatures of about 3.2 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, which is confirmed by the IPCC’s latest report.”

In light of the findings of the IPCC’s latest report, in addition to the sea level rise scenarios issued by the same body, the world must prepare for the fourth or fifth scenario, a significant rise in sea level, from 90 to 102 centimeters by 2100, from the water level in 2018.

Skea added: “This will lead to many risks, such as sea level rise, which will affect low-lying coastal areas and even threaten the existence of some countries and communities.”

21 cities in the Egyptian Delta threatened

To determine the extent of the impact of a one-meter rise in mean sea level by 2100 on the Nile Delta region of Egypt, we used the Flood tool powered by Google Earth and data from NASA, an open-source platform that identifies areas at risk of flooding with rising sea levels.

The maps revealed that 17 centers comprising 21 cities in Damietta, Kafr El-Sheikh, and Dakahlia governorates are at risk of flooding by 2100.

We consulted with a specialized researcher from the Faculty of Regional and Urban Planning at Cairo University to verify the accuracy of the results we obtained through the Flood tool.

We compared our artificial maps that predict the impact of a one-meter rise in sea level on the coastal cities of the Nile Delta region with manual maps designed for us by the researcher using the “placement” mechanism, and we observed a 95% match; our maps included one additional city, the city of “Fowah” in Kafr El-Sheikh governorate.

By analyzing the area data for the cities at risk of flooding, we found that the entire governorate of Damietta, two thirds of the area of Kafr El-Sheikh, and one third of the area of Dakahlia are at risk of Drowning, according to the 1-meter/2100 scenario.

The combined area at risk is equivalent to more than half of the area of the three governorates, and approximately one third of the area of the Nile Delta region.

These results also coincide with what was mentioned in the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report, when it placed the Nile Delta region of Egypt among three hotspots in the world, at high risk due to sea level rise.

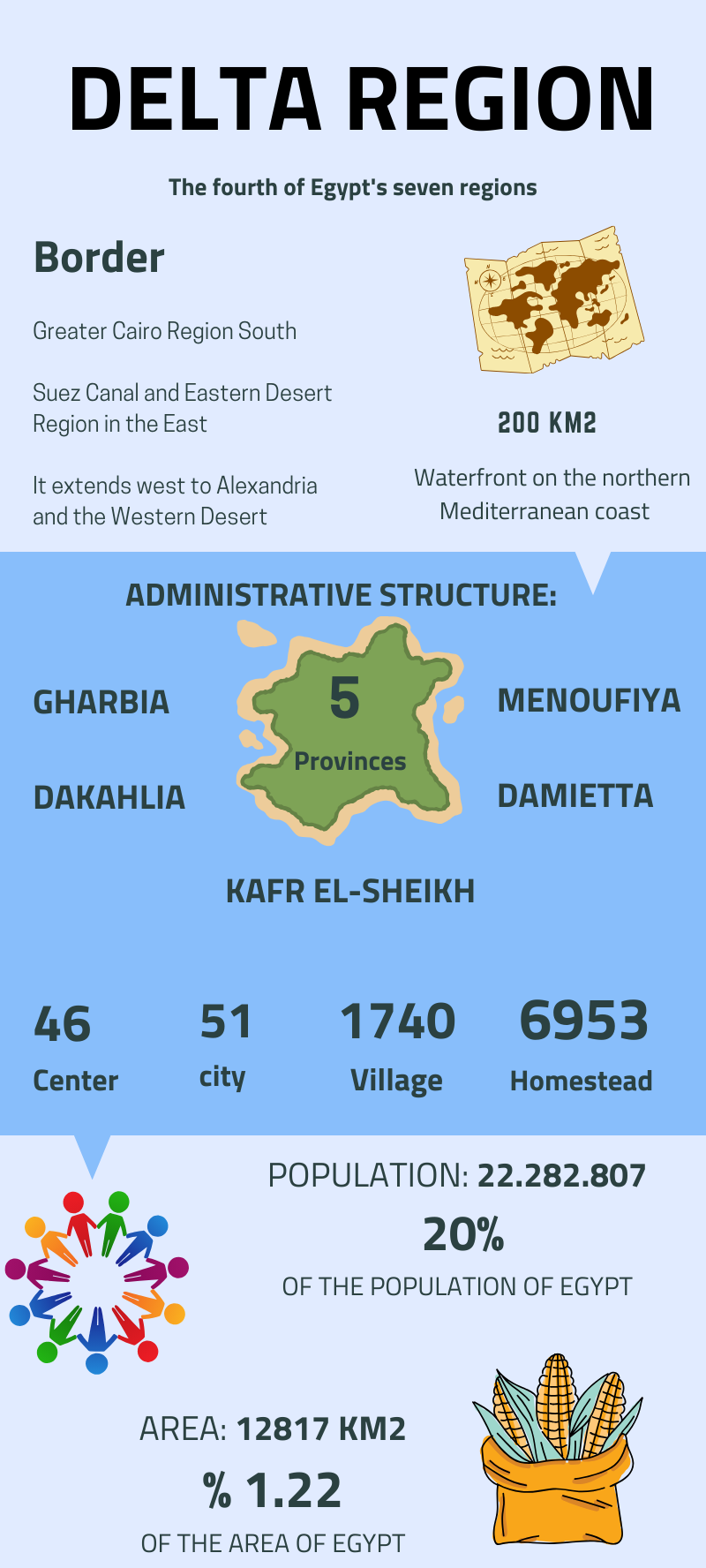

According to the development strategy for the governorates of the Republic, the Nile Delta region is the fourth of Egypt’s seven regions, with an area representing about 1.22% of the total area of the Republic, and a total population of over 22 million people.

One quarter of the area of the Nile Delta is at sea level or below, while the rates of land subsidence in the Delta range from 4.0 mm in the west to 3.4 mm in the east, annually, according to IPCC.

In the northern part of the region’s lands, which are generally agricultural, there are wetlands, lakes, and sand dunes. The northern coasts of the Delta are exposed to erosion, deposition, or coastal erosion.

Ahmed Abdel Kader, former head of the Egyptian General Authority for Coastal Protection, says: “The Nile Delta region is one of the most deltas in the world exposed to the effects of climate change, due to its low elevation relative to sea level, which exposes it to the risk of flooding. The impact of the phenomenon is confirmed and clear through maps and remote sensing.”

He adds: “Seawater has advanced more than three kilometers in the Delta’s coasts since the 1960s, and in the 1980s it swallowed (Rasheed Lighthouse), dating back to the 19th century due to the phenomenon of coastal erosion.”

Sea level rise is causing a number of impacts in the Nile Delta region, according to Dr. Abbas Al-Zaafrani, the former dean of the Faculty of Urban and Regional Planning in cairo university. These impacts include direct flooding of agricultural land and urban areas, saltwater intrusion into the groundwater, increased soil salinity, deterioration of the agricultural drainage system, especially lift irrigation, and flooding of lift stations.

Al-Zaafrani adds: “There is also a direct impact on ports and their land transportation networks, on the biological systems and fisheries in wetlands, in addition to the direct and indirect impacts on economic and social conditions.”

Millions of people under threat

The total population of the Nile Delta region is about 22.3 million, according to data from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, issued at the end of 2022.

Regarding the proportional distribution of the population of the region, 55% of them live in the three threatened governorates (Kafr El-sheikh, Damietta, and Dakahlia), with a total of about 12.2 million people.

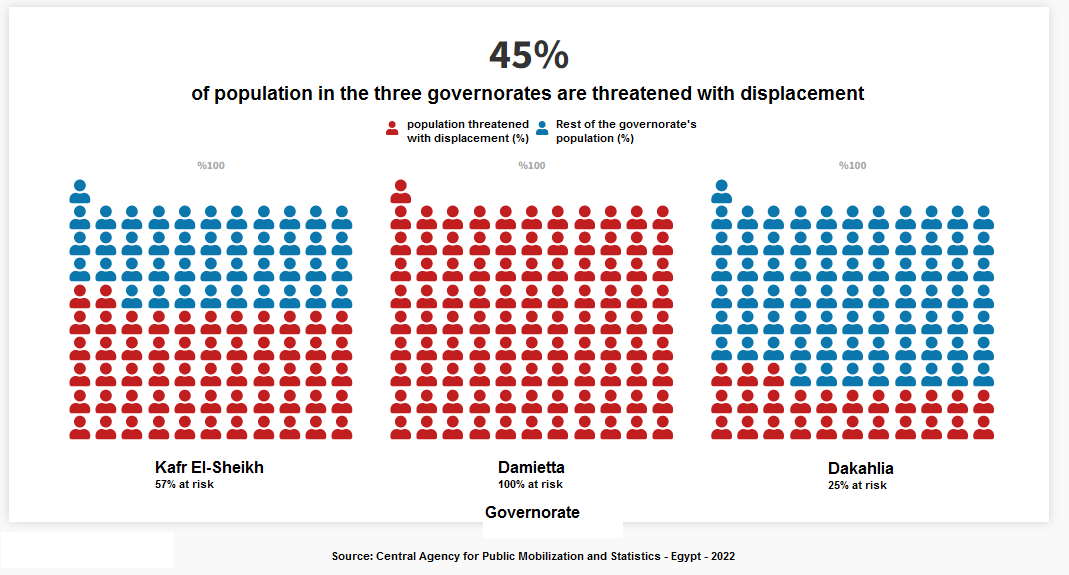

By analyzing the population data in the urban areas threatened by flooding, we found that the potential scenario of a 1 meter rise in sea level by 2100 threatens the lives and livelihoods of at least 5.5 million people, living in 21 urban areas, representing about 45% of the population of the three threatened governorates, 25% of the population of the Nile Delta region, and 5% of the total population of Egypt.

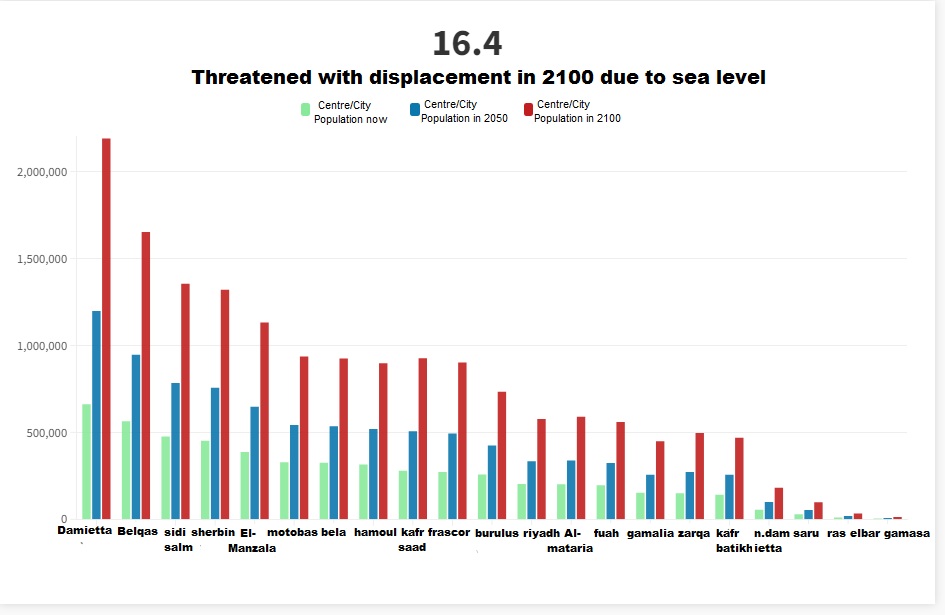

This number could double once in 2050, reaching 9.3 million people, and twice in 2100, reaching 16.4 million people, according to annual growth rates for each governorate, issued by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics in 2018.

Dr. Khaled Abudoah, an assistant professor of political sociology at Sohag University, says it is likely that climate pressures in these areas will lead to an increase in internal migration rates in Egypt, and displacement could cross geographic borders if pressures increase further.

He adds: “The issue of climate and environmental migration is not far from Egypt at all, and millions of people could be affected by rising sea levels, if they find themselves unable to live and earn a safe living in their geographical areas.”

The report issued by the International Organization for Migration in 2020 warns that rising sea levels and increased frequency of destructive climate phenomena are affecting human societies and could lead to unprecedented waves of migration and displacement of entire coastal populations, threatening the lives and stability of at least 40 million people.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 21.5 million people were forcibly displaced annually between 2008 and 2016 due to climate-related events, such as floods, storms, wildfires, and extreme temperatures.

It is estimated that climate migration will increase in the coming decades, reaching 1.2 billion people worldwide by 2050, according to the international think tank IEP.

On the other hand, the governorates of the Delta region already contribute to negative internal migration, as they have been sending migrants outside of them since the beginning of the twentieth century, according to a study published by Cairo University in 2010. Most of the migratory movement goes to the governorates of the Greater Cairo Region and the governorate of Alexandria, where the distance factor plays an important role in directing the movement of migration.

In the event of the “1 meter” scenario, whether in 2100 or before, the governorates of Greater Cairo and Alexandria will find themselves facing a flood of displaced people in search of stability and safety. Large numbers of them could also move to Mediterranean cities in Europe.

Land and food

The Delta region is Egypt’s breadbasket, and it still retains its relative advantage as the country’s only agricultural region to date, despite the steady increase in annual erosion rates of agricultural land, due to the rise in population growth rates on the one hand, and soil salinization due to rising sea levels on the other hand.

According to the United Nations Development Programme, the Nile Delta contributes about 20% of the country’s gross domestic product, through (agriculture, industry, and fishing). The Delta region includes about 27% of the area of arable land in Egypt, according to data from the 2019 publication on agricultural landholding and ownership.

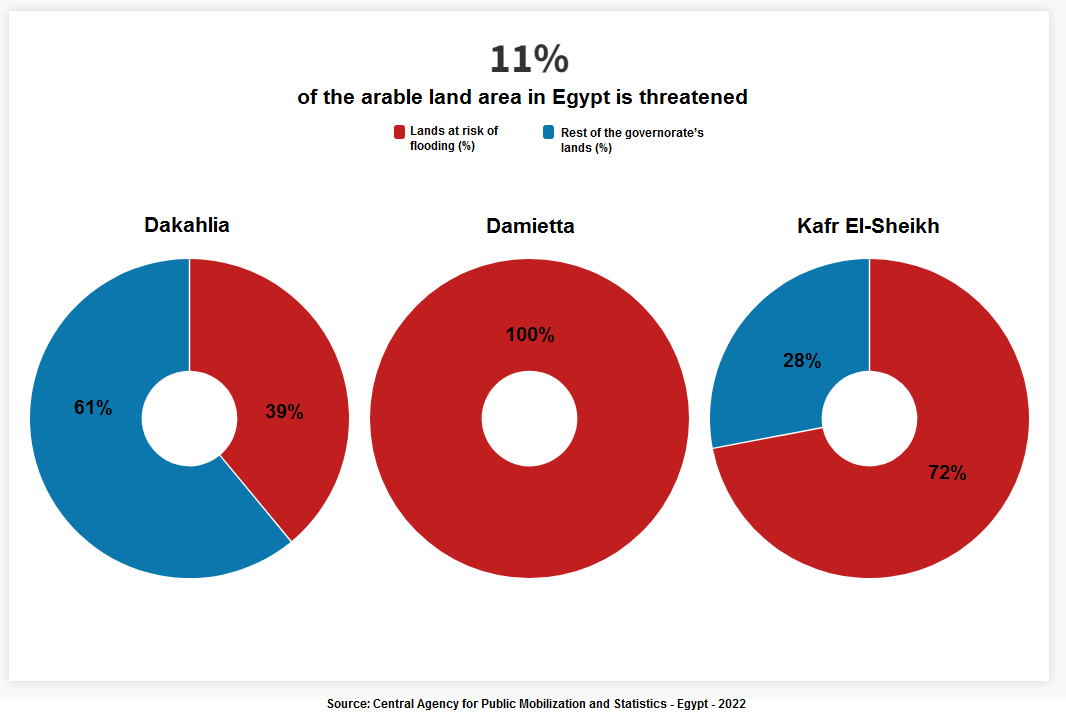

Based on an analysis of land use data in the governorates of the Nile Delta region, it is clear that agricultural land occupies an area of 2.5 million feddans, or 78% of the total area of the region. Agricultural land in 17 of the threatened cities is at risk of flooding or salinization if the sea level rise scenario of “1 meter” occurs, whether in 2100 or before.

We also found that the agricultural land at risk, according to the possible scenario, is about 976,000 feddans, or 60% of the total agricultural area in the governorates of (Kafr El-Sheikh, Damietta, and Daqahlia), equivalent to 39.5% of the agricultural land in the Nile Delta region, and 11% of the area of arable land in Egypt.

The researcher, Shaimaa Rabie, from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, confirms our findings, saying that: “The rise in sea level by one meter in the Nile Delta could lead to the loss of a third of the current agricultural land in the region.”

She also added: “It will also lead to the infiltration of salt water into the vast agricultural lands along the Nile Delta, threatening access to freshwater for drinking and agriculture.”

In 2019, a report by the Desert Research Center affiliated to the Ministry of Agriculture said that 25% of the cultivated lands in the Nile Delta region are already suffering from the problem of soil salinity, due to the rise in sea level in recent decades, with expectations of the problem worsening in the future.

As indicated in a report entitled (Human Development in Egypt 2021), issued by the Ministry of Planning and Economic Development in cooperation with the United Nations Development Programme, the infiltration of highly saline water into vast areas of the Delta due to rising sea levels will affect agricultural productivity, and wheat and rice production in Egypt may decrease by 15 and 11%, respectively, by 2050.

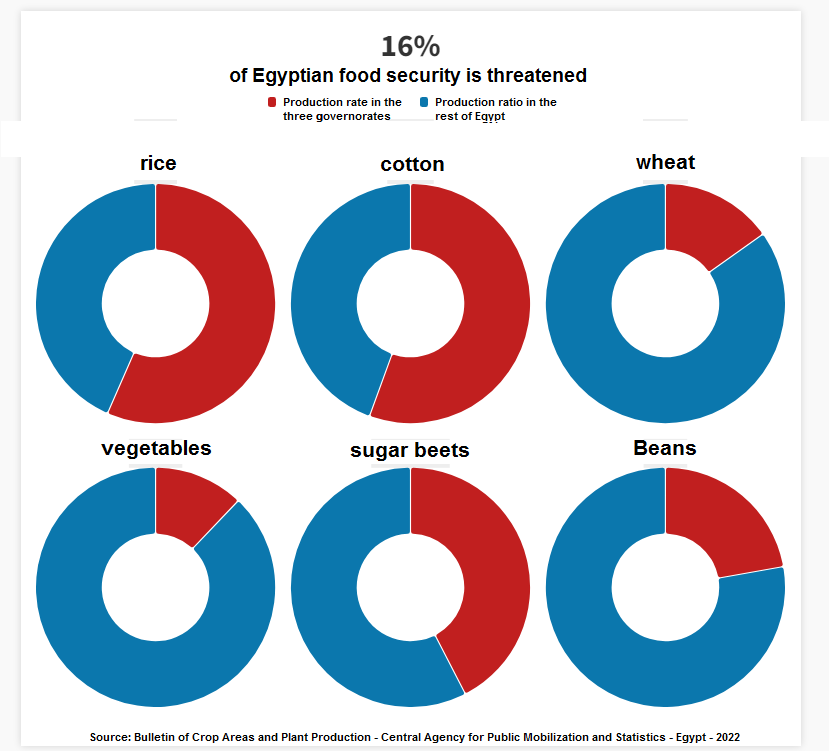

The threatened cities are located within three of Egypt’s most important agricultural governorates, and the most productive for strategic crops, such as (wheat, rice, sugar, beans, cotton), and multiple varieties of vegetables and field crops.

By analyzing the data, we found that the threat could affect 16% of Egypt’s production of six strategic crops, and this percentage could double in 2050 and 2100.

On the other hand, 5.2 million workers work in the agriculture and fishing sectors in Egypt, according to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics 2022. This means that the loss of this agricultural area due to climate change could threaten about 600,000 job opportunities. The number of those affected will of course double in 2050 or 2100.

Protection of the Delta Region

Egypt launched the (Egyptian National Climate Change Strategy 2050), at the end of November 2021, and included its vision for adaptation to climate change in all threatened areas, including the Delta region. The strategy, among its recommendations, urged the need to protect lowlands in coastal areas and the integrated management of these areas.

The strategy also pushed, within the proposed policies and enabling tools, towards studying the different solutions to adapt to sea level rise and protect coasts and coastal cities, such as: construction and architectural interventions, including traditional and non-traditional engineering protection works.

Following the launch of the strategy, the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation and the Egyptian General Authority for Coastal Protection, affiliated to it, began working on developing a comprehensive plan for the integrated management of coastal areas along the northern coast of Egypt on the Mediterranean Sea, in cooperation with the United Nations Development Programme and the Green Climate Fund.

The ministry has not yet completed the plan, and in spite of that, it has started implementing a number of adaptation projects in the Delta region according to an initial vision, until the plan is completed.

Mohamed Ghanem, the official spokesman for the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation, said that the Egyptian General Authority for Coastal Protection, affiliated to the ministry, is currently implementing projects to enhance adaptation to the effects of climate change on the northern coasts and the Nile Delta, to address sea level rise in five coastal governorates, namely: (Port Said, Damietta, Dakahlia, Kafr El Sheikh, and El Beheira).

The project includes the establishment of a data monitoring system on the Mediterranean coast, to be used in the work of the comprehensive plan. The plan, which is expected to be completed before the end of 2025, seeks to protect the natural resources and economic importance of the Egyptian coasts and their inhabitants, among other things.

The former national coordinator for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Dr. Hisham Issa, said: “The vision that the Ministry of Irrigation is adopting is good, and the projects that have begun to be implemented in the coastal governorates are an important step on the way, but they are not enough to repel the expected danger of rising sea levels on the region.”

He added: “The reason for this is that the required measures require a very large amount of funding, which is not available, due to the limited availability of external green funding, and the inability of the state budget to bear these amounts, which is a common phenomenon in many developing countries.”

Egypt needs about $113 billion to implement adaptation programs by 2050, according to the national strategy. This figure includes about $52 billion to adapt the agricultural sector, and $59 billion for the irrigation and water resources sector, which are the two sectors directly responsible for implementing the required adaptation measures in cities threatened by rising sea levels.

The national strategy acknowledges that the current available funding for the adaptation program is about $18.3 billion, and that the funding gap is about $94.7 billion, meaning that 84% of the required funding is not available yet.

Dr. Issa says: “The lack of funding for adaptation projects in developing countries is the responsibility of developed countries, especially the United States, which is historically responsible for the emissions that led to the climate crisis, and is obligated, according to international agreements, to finance the costs of addressing climate change in these countries.”

In 2009, at the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference, developed countries pledged to pay $100 billion annually by 2020 to developing countries for mitigation and adaptation to the effects of climate change, but they have not yet met their pledges.

The 2022 Adaptation Gap Report, issued by the United Nations Environment Programme, says that this figure is far below what is needed on the ground, and that annual adaptation needs are estimated to be around $160-340 billion by 2030, and $315-565 billion by 2050.

In addition to the lack of funding, there is another crisis, which is that the funding allocated to adaptation projects has accounted for only about 25% of the total limited funds available to address climate change, and the other 75% has been directed towards green technologies to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

This is clearly evident in Egypt’s share of funding from the Green Climate Fund, affiliated with the United Nations, which has not exceeded one adaptation project worth only $105 million, according to the fund’s official website.

Ambassador Mohamed Nasr, director of the Climate Change, Environment, and Sustainable Development Department at the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said: “The global private sector sees that adaptation projects have a social return rather than an economic one, and it lacks investment opportunities, while developed countries, which contribute to climate financing, consider adaptation projects part of development projects.”

He added: “Of course, this is not the case, adaptation projects have a developmental dimension, but they have other dimensions, and this is what we are trying to explain to developed countries.”

He emphasized: “If these projects are not implemented, their effects will go far beyond the idea of development at the local level. When the farmer loses the ability to adapt to climate change, and loses his source of income, he will look for a new source of income, or move to another place to look for a job opportunity, and if he does not find it, he will consider migrating to another region or country, and the numbers of illegal immigration in the world are a good evidence.”

Destiny

In 2011, Sabr Abdel Kafi succeeded in adapting to the effects of climate change, saving his land from salting. However, if the world’s countries do not commit to their climate commitments, perhaps by 2100, his descendants will jump on the nearest illegal immigration boat crossing the Mediterranean Sea, after the waters submerge their land completely.

This investigation was produced with the support of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ)